Episode Thirteen! Conversation with Tracey Baptiste

NOW AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBE ON ITUNES

Welcome to episode thirteen of our kidlitwomen* podcast! Every week this podcast will feature an essay about an issue in the children's literature community (Monday) and a discussion about the essay (Wednesday).

In this episode, Tracey Baptiste discusses her essay "THE MOVEMENT WILL FAIL WITHOUT INTERSECTIONALITY" (which can be heard in episode 12) with Jacqueline Davies. Tracey and Jacqueline discuss the intersectionality of the women's movement.

Read all the kidlitwomen* essays shared in March

Subscribe to the kidlitwomen* podcast on ITunes

On today's Podcast you will hear:

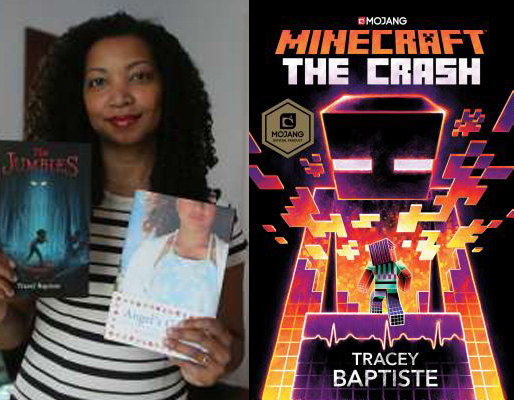

Tracey Baptiste is the New York Times bestselling author of Minecraft: The Crash, as well as the creepy Caribbean series The Jumbies, which includes The Jumbies (2015), Rise of the Jumbies (2017), and The Jumbie God’s Revenge (scheduled for 2019). She has also written the contemporary YA novel Angel’s Grace and 9 non-fiction books for kids in elementary through high school.

Tracey is a former elementary school teacher and is on the faculty at Lesley University’s Creative Writing MFA program.

Jacqueline Davies is the talented author of YA and middle grade novels as well as picture books. Her beloved The Lemonade War series, tells the story of a brother and sister who make a bet to see who can sell the most lemonade in five days. The second book in the series is The Lemonade Crime; the third book is The Bell Bandit; the fourth is The Candy Smash; and the fifth and final book in the series in The Magic Trap. Her newest book Nothing But Trouble (HarperCollins, 2016) tells the story of two smart girls in a small town who can't help but get into trouble by pulling pranks. See more about Jacqueline at her website.

TRANSCRIPT

Jackie: Hi, this is Jacqueline Davies, and I'm here today with Tracey Baptiste. And we're gonna be talking about her fantastic essay, "The Movement Will Fail Without Intersectionality." Hi Tracey, how are you?

Tracey: I'm good. Hi, Jackie.

Jackie: Thanks for being here with us. We're so happy to have you.

Tracey: [inaudible 00:00:18]

Jackie: I loved your essay. I think we should just dive right in. The place I think we should start is with the word intersectionality, which has found its way into kind of common parlance at this point. But I imagine there's still some people who aren't totally sure what it means, and that maybe it also means different things to different people. So I thought maybe you could start us off by giving your definition of intersectionality.

Tracey: Well the way that I think about intersectionality is literally the way that people think about themselves, all of the ways these things intersect. So for example, I am a woman, I am also an immigrant, I am both African American and of Indian heritage. So these are all of my different intersectional, the ways that I sort of consider myself. So when people think about intersectionality, they're thinking about where all of the different pieces, all of the different ways that people would consider them.

And the thing about intersectionality is that for a lot of marginalized people, it is a way to include things that may not have always been included. When you think about mainstream culture, you are thinking a lot of the time the default is white male. So an intersectionality would be female, a further intersectionality would be if you are male and you are an immigrant, if you are female and you are an immigrant. It's all of these different ways.

It's sort of odd, because it can be a way that we separate each other, but because some people have always been left out of conversation when we are thinking about things, it's also a way to call attention to, well let's think about how this works for this community, for example if you have a disability. How is the conversation working if you are disabled? How is the conversation working for you if you are all of these other things?

Jackie: Yeah, it's interesting. So really the root of it, it's about identity.

Tracey: Right.

Jackie: It's about our personal identities, and I think what you said is so important. There's a way in which you can look at it as slicing and dicing and getting everybody broken down into little pieces. But what intersectionality I think is really about is the inclusion part, is about bringing all the pieces together into more of a whole.

Tracey: Right, yes.

Jackie: Right. So in your essay, you talk about the power differential, which I think many of us experience, we understand. But you also say, "because the patriarchy has some of us in its grip," and I was wondering if you feel that yourself. Are there ways in which you feel that you are still in the grip of the patriarchy, and if you have any specific thoughts about that?

Tracey: Oh, that is absolutely true. I think there is no way really to escape the culture in which you are born. So I think that we all have things that we have to check ourselves on all the time. As I mentioned, I'm an immigrant, I was born and raised in the Caribbean. And if there is not a patriarchy in the Caribbean, there is no patriarchy anywhere. [inaudible 00:04:20]

Jackie: And you just came back from a trip, right?

Tracey: I did. I was-

Jackie: So there you were, you were in the midst of it.

Tracey: Exactly. I was in the midst of the patriarchy last week for Bocas Lit Fest, and it's still very much alive and well, well men rule, women are there to serve men. What a woman desires is secondary to what a man desires. That is still very, very, very much the culture there. So I do find myself having to check myself on that all the time. I find that, especially in familial relationships, when we are talking about the boys versus when we are talking about the girls, I have to be careful. I'm more aware then. I'm more aware of the ways that we talk about boys and the ways that we talk about girls.

There was actually a recent conversation that I had about, not to get gross, but hair removal. You know, like whether we're shaving our legs or not. And this is a conversation that is happening in front of my son, and my son was like, you know, why do you have to shave your legs? So there's all of these little things, like what does society expect, what does society put on us, what do we put on ourselves? I buy into a lot of it. There's a lot of things that I buy into, and I have to think about whether or not I really should. I mean, why do I shave my legs? Do I have to? [crosstalk 00:06:02]

Jackie: Yeah. And it's really about, yeah, right. It's really about awareness. I think we're all so much products of the environment that we grow up. And it does come out more in family, I think you're absolutely right about that. There's something about family that always seems to take us back, a little bit regressive.

Tracey: Yes.

Jackie: Now you bring up some really interesting, and again, specific situations in which you've been sort of challenged by people in terms of intersectionality. And there's just one that I'm going to bring up. You're talking about how sometimes you've had the situation where people, I'm going to say white women, because that's really what we're focusing on in this essay I think mostly, the intersectionality between white women and women of color. So you talk about white women "whip up a diversity festival only to notice that there are only white people in charge, and then reach out to me because of my hue." So there's an instance, a situation that you've actually been in. How would you like white women or people putting together these diversity panels, how you like them to handle this? What advice would you like to give to them?

Tracey: Well, I've had this both ways. I had it where people have reached out to me towards the tail end of things, as a, oh shucks, I forgot to add some people of color.

Jackie: I forgot to check that box.

Tracey: Right. But I have also had people reach out to me early, and say that, I want to do a thing, and I'm trying to make it as inclusive as possible. So I'm reaching out to you, and if you have any suggestions of people that I can also reach out to, then please let me know. So I think this is the way. I think the way is to start by thinking about who needs to have voice in this conversation as we start building this thing, before you start building and then realize, oh, one of the legs out of the thing that I'm building is missing.

Jackie: Yeah.

Tracey: You know, or two of the, how many ever. So I think the way to do this is to start when you're thinking about the thing, think about all of the stuff that might be missing, and all of the people who might be missing, all of the people who need to have voice in this conversation. And then go from there. When you're starting out, just start out the right way, and then you don't have to worry about it later.

Jackie: Right. You and I met because we were on a panel together. And I was putting together that panel, and I remember specifically, it was at a specific conference and specifically I knew the topic I wanted to talk about. I wanted to talk about family middle grade. So that was sort of my first comb through of all the people attending the conference. I said, okay, who has really excellent books that talk about family middle grade. You have "The Jumbies" of course, so that just jumped right out at me. And then there was a second layer of reflection for me of saying, I want to make sure that there's at least one out of a three person panel, at least one person of color.

So I reached out to you, I reached out to another author. Do you feel like we needed to have, when I approached you, do you feel like it would have been better if we'd had a more explicit discussion about the choice of the panel, or? Because I've heard this from other people as well, that they wish that when they're approached to be on a panel, that the person would just come right out and say, diversity is important to me, and I'd really like you to be part of this panel. Do you feel like that needs to be said explicitly?

Tracey: You know, I don't know that it does. I just came from a panel this morning, we had to go out to Long Island, the New York Librarian Association was having a conference, and I didn't ask anything about that panel. It was led by Ellen Oh, and the other participants were [inaudible 00:10:17]. So the thing is, once I see who's on a panel, I know whether or not diversity is important to you or not. That's a fairly easy thing to suss out once I've been asked.

So I don't need to have that conversation unless I notice that I've been invited to a panel and all of the participants are white, or all of the participants are male, and it's just me by myself. That's not a comfortable situation for me, and that is the point at which I either say, hey how about we add this person or that person to the panel, or, did you plan on asking other people of color or other women? You know, I sort of look at the other panelists and raise a red flag. And if that's not something that they can add or something that they can do, I am happy to bow out.

Jackie: Yeah, it must feel tiresome to you to feel like you have to be the one starting that conversation.

Tracey: It is extremely exhausting to always have to do that. But at the same time, nothing is going to change unless this conversation happens. So yes, there are times when it is just exhausting. And there are times when I have done these panels, that I'm the only one, or I'm the only person of color. And I hate those panels. They're always much more stressful to me than the panel I did this morning. I was completely relaxed this morning. Usually I have some winding down time that I need to do after I [inaudible 00:11:57] event, and I didn't this morning.

And I realize it was because I felt perfectly comfortable in that panel. So yeah, it can go either way. If you want to have that conversation at the beginning, then I know and it's great. If you don't have that conversation, but you do have the diversity, we don't have anything to discuss. There's no discussion that needs to be had. If you don't, then yes I'm going to bring it up. If that's not a course that can be corrected, I may have to bow out.

Jackie: Right. In your essay, you bring up some of the thinking that might be going on with white women in the women's movement. And you talk about that there are these two possibilities. You say, "Maybe the belief is that the power imbalance between men and women hurts them, but the power imbalance between white and not white and others doesn't affect them. Or that other types of imbalance actually put them at an advantage." Which in a way is sort of two sides of the same coin.

One is that they're not particularly disadvantaged by one thing, or they realize that they are advantaged by something. Do you think that another piece of this, another important piece of this, is that white people are recognizing the imbalance, but they're minimizing it? They're just not seeing it as radically important as it is? Do you think it's not that they're not seeing it, but that they're not seeing how big it is?

Tracey: I think that people are selfish, people think about themselves first.

Jackie: Sure.

Tracey: And then our own sort of group first. So it's like, you first, then the people in your house, then the people who are related to you. It sort of goes out like that, like these big concentric circles of where your concern lies. So I think that people may not always recognize, and in this case by people I mean all people, may not always recognize the marginalization of other people. It's not that recognizable because they don't personally experience it. So then when they start to experience or notice, and it has to be pointed out, I don't think that really it is that automatic for people to recognize the pain of others as groups, in big groups, outside of who they are.

I think once you notice it, once you do, you're like, oh wait, hold on. This isn't right, or this isn't good, or whatever it is. And you start to notice it, you still kind of have to train yourself to keep noticing it, because it's easy for you to kind of fall back into your default, which is worrying about yourself. So I think that people do understand that there is marginalization, but they kind of default to who they are, they default to what their concerns are. And it is extremely difficult to always be thinking about people who are outside of your, I guess home group is the way I would think about it.

So it's not so much that I think that people are sort of deliberately trying to, well that's not true. I think it is possible that there are people who are deliberately trying to minimize it because they want to dismiss a group, or they feel that they need more attention, or whatever. So I think that there is deliberate minimization that happens in people's minds. But I also think that sometimes it's really, you have your own stuff going on, and it's hard for you to think like that.

But the fact is, in the kind of world that we live in now where, I mean the world is global now, it is not really in these small encapsulated spaces anymore, especially with social media, especially with the ability to travel widely. It is dumb, it really is kind of dumb. And the fact is, if you do have to train yourself to think differently, to look at things differently, to when you see something happen to really examine it, if that is a thing that you have to do, you should be doing that. You should be doing it all the time.

Jackie: You use a wonderful phrase, "willful ignorance." And I love that phrase, because ignorance we think of as just being something, well you haven't been taught about something so you're ignorant about it.

Tracey: Right.

Jackie: But willful brings a whole other level to it. And I think especially when you talk about the ways in which we move in and out of each other's lives through social media, through all the ways that boundaries are expanding, there does come a point when you can't pretend not to know anymore.

Tracey: That's right. That's exactly right. And that's basically what I was just talking about is that now that we do have this global space that we all play in, that we all work in, that we all exist in, we're all colliding at the time. You cannot not notice that there are other people who have different opportunities that are open to them, who have different ways that the larger culture treats them. You cannot not notice these things and pretend that, oh everybody has an equal shot. That I think is where I feel the idea of willful ignorance comes in, because it is happening all around you. And for you to say that it's not happening when it clearly is, you can literally point your body in any direction and see what is happening in society, how do you justify ignoring it?

Jackie: You raise a really intriguing question in your essay. You ask, "Where would we be if women's movements had always been intersectional?" And I'm wondering if you can tell us what you think are some of the reasons for the failure of the woman's movement to be more intersectional?

Tracey: You know, the thing that I go back to always is suffrage, is the suffrage movement when women were trying to get the vote, because it was the only way that they could have a voice in anything, in public discourse really. So there were families, men who were the head of the household were voting on behalf of the women of the household, and the idea was that women wanted to have their own voices. What happened with the women's suffrage movement in the United States was that all of the women who were working towards it, it was fine while the idea was women's suffrage, and then it turned out to be white women's suffrage because white women got the vote, and other women still remained marginalized.

And those women, we still are out here celebrating these women, and they were happy to leave black women, women of color, behind so that they could have their say. And at that point, what you are looking for if you are this person who wants to leave other out, you are not looking for equality. The argument was, it wasn't about women's rights, it was women's equality. But what they actually were looking for was power, because if everyone does not have an equal shot, it means that some have power over others. And if you are okay with that, equality is not your goal, your goal is power.

Jackie: Right. Are you still talking specifically about the suffragist movement back in the 1800's?

Tracey: [inaudible 00:21:01]

Jackie: Because we see it coming up, it came up again in the '70s, it came up just most recently with the women's march. The same issues are coming up.

Tracey: With the women's march, yes. Yeah, I tend to go to the historical reference, because I find that it's irrefutable. It's irrefutable what happened with the women's suffrage movement. But the thing that happened with the women's march is that once again white women took the helm, even with the Me Too movement. Who showed up on the cover of, what was it, Time Magazine? When it was a black woman who started it? You know, Tarana Burke was the woman who started, and she was nowhere on that cover. She appeared in a later cover. But white women kind of took over, and they became the face of that movement.

And the fact is, the Me Too movement, which is still ongoing, and we all know it, is mostly going to benefit white women. And black women, women of color, women who are marginalized, women who have mental disabilities, physical disabilities, and so on, will still be left out of that conversation. This all started with Harvey Weinstein and a bunch of white women coming forward and saying that this man abused them. That would not have happened if it was a black woman, or a woman with a mental disability, or a woman who was disabled. It just would not have. They just don't have that kind of voice.

And so when people talk about women's movements, people talk about let's say the need for women to be paid the same as men, a lot of the time they don't remember to say, to quote the facts that black women, Latina women, women with mental or physical disabilities, are paid at even lower rates. So any time we're having this conversation, you have to remember all of the other people who need to come on board. It is not just white able bodied women who are fighting for equality. There are all other kinds of women. And the thing is, if you bring everybody along, you have far more people backing you.

You have far more people as part of a movement, and then you don't have this fracturing, which is what happens. The feminist movement, for example, there are women who do not consider themselves feminists. Rather, they consider themselves womanists, because they feel that the feminist movement centers white women, and that other women are left out of it. And so they consider themselves to be womanist instead of feminist. So you already have a huge segment of people who could be all working together kind of fractured.

Jackie: Right. So these are some of the things you mean when you say, "the refusal to be intersectional." These are some of the examples of what you're talking about.

Tracey: Yes.

Jackie: Active refusal to include, to always include people who fall outside of the much smaller, I'm thinking of a Venn diagram, white women-

Tracey: Right, yes.

Jackie: Keep bringing in the other circles so that we see more and more overlap.

Tracey: Exactly, yep.

Jackie: Can I just, I'd love to veer off for just one minute before we get to our closing questions. There was what I thought was a terrific essay in the Sunday Review in The New York Times back in December by Angela Peoples. The title of it is "Don't Just Thank Black Women, Follow Us." I don't know if you happened to see it.

Tracey: No, I don't remember that. Maybe I did, but I don't recall it.

Jackie: It's a terrific exploration of some of the recent elections that have happened in the United States, some of the special elections, focusing specifically on the one in Alabama where Roy Moore was challenged by Doug Jones, and Doug Jones ended up winning in large part because there was a historic turnout of black voters, and specifically black women.

Tracey: Right.

Jackie: They voted, 98% cast ballots for the Democratic candidate, Mr. Jones. She closes her piece with this two sentences, and I'd like to read them, and I'd just like to hear what you think about them. This is what Angela Peoples wrote. "Black women are being widely credited for saving the day in Alabama, and that credit is one small step in the right direction. But we don't need thanks, we need you to get out of the way and follow our lead." What do you think of that?

Tracey: I think that that's accurate, I really do. The fact is, even specifically in that particular election, but if you look at the general election as well, overwhelmingly the black women voted Democrat. Overwhelmingly black women are on the side of liberal ideas, progressive ideas. And the fact is, as much as anybody wants to think differently, we are always heading in the direction of more liberal and more progressive ideas. Regardless of what you think, regardless of whether you are a conservative or not, and I actually come from a fairly conservative family, we are always headed in that direction. And the people who are leading us in that direction are always black women. So I say yeah, put black women in charge of everything, I'm telling you that.

Jackie: You know, there's a way in which one wonders if white women will ever be able to truly understand the adjustment that they need to make to their own position unless they just get out of the way. Just like, move to the side and realize that they're not the leaders any more, and let somebody else, black women, take the lead. And then that might be the thing that actually shakes them loose from the ideas of what feminism is and what it's been for a long time.

Tracey: It might be. I don't know what it would take for all of us to come together and to figure it out for ourselves. I really don't know what it would take, or how that would need to happen. These are not ideas that I really have solidified or things that I have really figured out for myself. But I think we do get in each other's way. I think we do get in our own way all the time, often, and even personally. I mean, you know that. Like personally, we get in our own way all the time. Just even finding regular success in this crazy industry, we get in our own way all the time.

And if we sort of take a step back and look at the facts, look at the figures, which is always what I want to do. I always want to step back, take a look at the facts. What are the facts, what are the figures, what is the history here? Examine it that way, because that is the stuff that you cannot argue with. And leave the emotional part out of it. And then where are we heading? And the fact is, yes, black women have been sort of leading us down the right path.

Jackie: Right. This has been a terrific conversation I've really enjoyed. Before we go, I would like to ask you a couple of questions. The first is, I would just love to know if there's anything that you're working on at the moment, any project that you're particularly excited about that you'd like to just tell a little bit about? We'd love to hear it.

Tracey: Oh sure. So I actually have a lot on the docket currently. I have three different projects that I'm working on. But the one that I can, you know how it is. You can't actually say anything.

Jackie: It's a secret.

Tracey: There is a secret. But the thing that I can announce is that my new novel is an official Minecraft book.

Jackie: Oh, fantastic.

Tracey: I know, it's called "The Crash," and it comes out on July 10th.

Jackie: Fabulous. Oh that will be a good one to look forward to. And finally, because we are in this whole month of March, where people were writing essays and women were talking about issues of interest to them, one of the things that we were always pushing for was reach for the stars. Like break from your boundaries, say what you want. So I'd like to ask you, what at this point in your career if you could have anything, reach for the stars, be crazy, what would that be?

Tracey: I would like to have a private jet.

Jackie: A private jet. That's fantastic, that's great.

Tracey: Yeah, I'd like to have a jet that takes me all of the places that I need to go, so that I never have to fly commercial again.

Jackie: Wouldn't that be amazing.

Tracey: And I would fly it myself. I took pilot lessons when I was a teenager.

Jackie: Seriously?

Tracey: So I could like finish, I did. So I could like finish my pilot's license and [inaudible 00:30:38].

Jackie: But wouldn't you so prefer to have somebody else flying you? To me, that would be the luxury-

Tracey: Well yeah-

Jackie: Is to have somebody else, I'd go take a nap.

Tracey: Yeah, I would prefer to have somebody else fly it, but I could technically do it myself.

Jackie: That is awesome. That is terrific. Tracey Batiste, thank you so much for being here with us today. It's been a real pleasure.

Tracey: Thank you, Jacqueline. Thank you very much for having me.

Jackie: You're welcome, take care. Bye bye.

Tracey: Okay, bye.